This huge flying boat had a wingspan of 126 feet and was crewed by five US Navy aviators and one US Coast Guardsman. The flight’s 100th anniversary was celebrated in 2019.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the Assistant Secretary of the Navy at the time – and future president – enthusiastically supported the attempt to cross the Atlantic by air. One of the Navy men involved in the planning told him: “We’re going through an awful lot of red tape to get the money we need to buy parts.“ Roosevelt replied: “I have the authority to approve purchase orders up to a thousand dollars. When you need more than that, just ask me twice.”

The four flying boats were designed and built by the Glenn Curtiss Aeroplane Company with a crew of 6 aboard each aircraft. They were numbered the NC-1….NC-2….NC-3….and NC-4. The designation “NC” derived from “Navy” and “Curtiss.” The crew affectionately called them “Nancies.”

●We will ship directly to anyone on your list along with a greeting from you.

The trans-Atlantic flight began at Rockaway Beach in Queens, NY, but not before the NC-2 broke loose from her moorings in a storm and smashed into a pier. Since there were no sophisticated navigational aids in 1919, the three remaining flying boats were guided by 47 U.S. Navy warships stationed strategically across the Atlantic. They were brightly illuminated at night and used smoke trails by day to keep the aircraft on course and were always ready to rescue the aviators in case of emergency.

The flight was plagued by unpredictable weather and mechanical failures which downed one of the flying boats in the ocean for two days. Repairs were made in rolling waves as high as 30 feet. The crews endured unbelievable hardships and as one crew member put it: “With the help of God and in spite of the devil, we’re going to do this little thing.”

Just 200 miles from safe harbor at the western islands of the Azores, the NC-1 and NC-3, flying together, ran into trouble. Due to very heavy fog, both commanders decided to land but, because of the near-zero visibility, they didn’t see the towering waves until the last minute. With great skill and some luck, they put down but were battered by the heavy seas. The crews saw and heard the damage done to their aircraft by the relentless waves. They lost sight of each other and were on their own.

The NC-1 crew kept one engine running for steerage and threw out sea anchors to keep from being swamped but the anchor ropes snapped like threads. Each rolling wave dumped more seawater on board but the bilge pumps couldn’t keep up. They barely survived the night. The morning was free from fog but the wind and waves continued. The situation looked hopeless when the crew was startled by a ship’s horn directly behind them – a freighter. The Greek ship, Ionia, rescued the NC-1 crew and tried towing the craft to safe harbor but the tow rope broke. Since it was a danger to ship traffic, the commander of the NC-1 ordered that it be rammed by the freighter. It sank in deep water.

Meanwhile, the NC-3 was still at the mercy of the high winds, rain and relentless 30 foot waves. The crew was wet, cold and hungry but determined to overcome the never-ending pounding of the sea. They hoped the southwest winds and the use of their engines would eventually carry them to landfall, if the hull didn’t break apart before then. Just 10 miles from their original destination in the Azores, they were sighted by the U.S. destroyer “Harding” and although the aircraft wasn’t airworthy, the crew wouldn’t abandon it. They limped into port while every ship’s horn blasted a greeting and cheering crowds lined the shore. After 60 hours and 200 miles of a nightmare at sea, “the Three” was broken – but not the crew.

That left it up to the 6 men aboard the NC-4 but they had their own problems. At one point, it was virtually lost in the zero-zero fog – so thick the crew couldn’t see from one end of the aircraft to the other. The pilot was totally disoriented and almost put “the Four” into a spin, but he recovered. The radio officer finally picked up bearings and weather information from a destroyer hidden below in the fog.

The NC-4 flew on to complete history’s first aerial crossing of the Atlantic – landing at Lisbon, Portugal on May 27, 1919. It then diverted to Plymouth, England, as a “tip of the hat” to the town from which the pilgrims sailed the Atlantic to America in 1620 – 299 years earlier. The flight was a point of pride for naval aviation and was front-page news in cities across the U.S. and around the world.

The 100th anniversary of the Curtiss NC-4 flight was celebrated on May 27, 2019. It was an amazing achievement by 6 remarkable men.

The Smithsonian acquired the NC-4 in 1926 and a 4-square-inch section of the original wing fabric from their restoration is attached to your 15″ x 20″ aviation relic print. Because of its constant exposure to seawater and weather, the wing fabric of the NC-4 was coated with spar varnish to which pigments were added – each fabric swatch still has that original, golden-brown color. Also included is a Certificate of Authenticity signed by the Deputy-Director of the National Air and Space Museum – along with 2 pages of colorful historical information on the flight and aircraft specs.

●Want to send a gift for Christmas or other special occasion? We will ship directly to them and include a message from you.

●FREE SHIPPING through December 25 on your order of two or more relic prints – mix or match.

The commander of the NC-4 was LCDR Albert Read, USN. Although a small man at 5” 4” and 120 pounds, he was respected, admired and large in the eyes of his crew. He held pilot license #43 with the U.S. Navy and was considered to be the best navigator they had – a talent that would pay off on the flight. Read was nicknamed “Putty” because his face rarely showed emotion or panic, even in dangerous situations. Read distinguished himself during World War II in naval aviation and retired as a rear admiral in 1946.

The pilot was the only U.S. Coast Guardsman aboard – Lt. Elmer Stone. He was a pioneer in USCG aviation and convinced others of its importance for the coast guard’s mission of rescue and law enforcement. He distinguished himself during the flight and, along with the other crew members, was awarded the U.S. Navy Cross and a commemorative NC-4 medal struck by Congress and presented by President Hoover.

The co pilot was Lt. (j.g.) Walter Hinton USN. As a youth, he saw a poster urging young men to “Join the Navy and See the World.” He did just that and with a fascination for flying, went into naval aviation. In his later years, he was a special guest on an early trans-Atlantic flight in a Concorde. His hazardous flight in the NC-4 took 19 days – the supersonic Concorde flight was less than 4 stress-free hours.

The engineer was Lt. James Breese, USN. In 1954, he was on a business flight to Europe and asked by a flight attendant if it was his first overseas flight. She was intrigued by his reply: “I flew the Atlantic once before, 35 years ago.” Puzzled, she mentioned it to the pilot who knew about the historic 1919 flight and invited Breese to the cabin.

Ensign Herbert Rodd, USN was the radio officer. He was an important crew member since he was the link to the outside world and the one to alert rescue ships of their inflight emergencies and location. On one worry-free leg of the flight, he was asked by Lt. Breese to send his wife a message. Rodd said that he couldn’t because: “I tried to send one to my girl but the Marconi telegraph man couldn’t accept it since there were no rates listed for messages from airplanes.”

Chief Machinist Mate Eugene Rhoads, USN was the sixth crew member of the NC-4 and the only enlisted man. Rhoads was a key member of the crew and the go-to-guy when engine or other mechanical problems put the flight at risk.

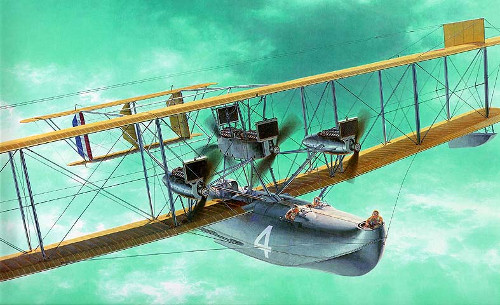

Notice in the images on this page that five of the crew members were in cockpits open to whatever the weather had to offer. The commander-navigator sat in the nose of the NC-4. The two pilots were positioned 12 feet behind him. The engineer and radio officer were in the rear cockpit, 3/4 of the way back. The technician-mechanic was aft – inside the hull.

During World War I, German submarines were dominating the North Atlantic where they were sinking American troop and cargo ships virtually unchallenged. The U.S. Navy embarked on a bold plan to design and build a dependable, combat-ready aircraft that was also sea-worthy – to help turn the tide against the German U-boats. The NC flying boat was born, but the war ended before being deployed.

During World War I, German submarines were dominating the North Atlantic where they were sinking American troop and cargo ships virtually unchallenged. The U.S. Navy embarked on a bold plan to design and build a dependable, combat-ready aircraft that was also sea-worthy – to help turn the tide against the German U-boats. The NC flying boat was born, but the war ended before being deployed.

The NC-4 was huge by any standard, standing 24 feet high, with an upper wingspan of 126 feet and powered by four 400 hp, V-12, Liberty engines. The engineers and contractors were startled when the Navy brass told them: “I don’t know exactly how to put this, but the admiral wants a seaplane that can fly the Atlantic.” That was quite an order. It was just 16 years since the Wright Brothers’ first flight at Kitty Hawk went 120 feet – less than the wingspan of the proposed seaplane.

The best minds went to work. Many of the details were turned over to the Curtiss Aeroplane Co. team but there was an argument about the hull design. The Navy wanted the hull to be both a flight cabin and a boat but also lightweight and sturdy. A talented Navy design engineer proposed a 45 foot hull with a 10 foot beam but one critic said: “I would feel safer in a peanut shell.” The Navy engineer won the argument and built the hull himself – by hand. Each of the four aircraft was delivered at a cost of $100,000 – the equivalent of $1.5M today.

Weight was an all-important concern for the flying boats. The operational weight of the NC-4 was a whopping 28,000 pounds and so every effort was made to “lose some weight.” The use of aluminum in the fuel and oil tanks on the Four was the first large-scale application of the metal in aviation and with the help of ALCOA – Aluminum Co. of America – each 200 gallon fuel tank weighed only 70 pounds, saving a total of 630 pounds compared to equivalent steel tanks.